Placing a patch as a cosmetic enhancement developed from an earlier medicinal use.

Medical texts advise that plasters – linen bandages spread with salves and ointments – could be set on wounds and sores, or placed on what we might call pressure points to alleviate things like head colds and migraines.

Early instances of fashionable patch-wearing, particularly in the sixteenth century, allude to this medical use while also suggesting a growing fad.1 In Westward Ho, a play by Thomas Dekker and John Webster published in 1607 though performed before this, a character called Judith complains to her husband that she’s troubled with a cold, a ‘rheum’. Her husband replies, ‘How often have I told you, you must get a patch.’ To which Judith muses to herself, ‘I think when all’s done I must follow his counsel, and take a patch, I have had one long ‘ere this, but for disfiguring my face: yet I had noted that a mastic patch upon some women’s temples, hath been the very rheum of beauty.’2

Look Closer…

This portrait is one of the earliest visual examples of patch-wearing in England. The sitter’s cheeks appear to be rouged and she has a large, black patch on her right temple – a placement believed to enhance the attraction of the eye and whiteness of the skin, but also to cure migraines.

Amidst figural and animal motifs, the splendid embroidery of the lady’s waistcoat shows symbols of love such as violets, strawberries and bows, all sprouting forth from interlocking, leafy branches. Observe the strawberry next to the finger on her right hand. It has switched from being an embroidered motif to looking like a three-dimensional object. Is this a painterly device to highlight the vows tied to a wedding ring?

Significantly, the strawberry was an attribute of Venus, goddess of love, who, incidentally, also had a flattering mole on her cheek. If the lady presents herself as an alternative Venus, the patch, as the theme of love, has many implications.

Patches might also be worn by men to simultaneously hide a scar – a manly, honourable token of battle – and advertise its presence. Here again the medical and the cosmetic merge.

Look Closer…

The lunette patch below Lord Cathcart’s right eye covers the scar of a wound he obtained during the battle of Fontenoy in Flanders on 11 May 1745.

Joshua Reynolds portrays him as a gentleman in luxuriously embroidered coat and lace cuffs, wearing a powdered and carefully pomaded wig. Yet the armour underneath and the patch on his cheek interrupt this air of gentility. The patch is a literal result of the sitter’s bloody pursuits on the battlefield. In short, it is not only a cosmetic concealer, but a badge of honour proudly displayed.

In instances like this, patches became a striking part of self-presentation. Bishop Peter Mews (1619–1706) is an unlikely example. As a young man, almost certainly before his ordination, he had fought in the royalist forces during the English Civil War. He was wounded more than once and taken prisoner too. Decades later, by now a bishop, this martially minded man of God hurried to the support of the government forces during the Monmouth rebellion. Again he was wounded in the fighting. The portraits of Peter Mews, of which there are several, show him wearing a prominent patch over a facial battle scar. This gave rise to his nickname: Old Patch.3

Look Closer…

Peter Mews had a choice as to whether he was portrayed from the three-quarter left or right side. Fixing on the latter partially hides the patch that gave rise to his soubriquet and thus makes its appearance more accidental and ’natural’.

A full and direct view of the patch could perhaps harbour a whiff of vanity and pride, attributes not fitting for a servant of God.

Although it can be difficult to tell from both textual and pictorial sources whether any given use of patches is primarily for health or for beautification, it’s clear that by the mid-sixteenth century, patching for fashion was a spreading vogue.

Look Closer…

In the late seventeenth century, fashion media developed rapidly. Paris became the hub, publishing fashion plates and life-style magazines that promoted fashions in ever quicker, contrived cycles of time, and that were of interest to more than just society’s elite.

This fashion plate shows that extensive patching was an integral part of the latest fashion for the winter season 1694. This plate, however, shows French patching practices. These were not necessarily followed elsewhere.

In England there are relatively few visual depictions of patched faces. But Samuel Pepys, whose diaries tell us so much, does paint us a word picture of different types of patch-wearing.

Following a cold he has a scabby mouth, ‘so that I was forced to wear a great black patch’. One day he sees the Duke of York, who has ‘two or three patches upon his nose and about his right eye, which came from his being struck with the bow [bough] of a tree the other day in his hunting’. The case of Margret Cavendish, the idiosyncratic Duchess of Newcastle whom Pepys was determined to see for himself, seems to lie half-way between the medical and the cosmetic. She had, Pepys writes, ‘many black patches because of pimples about her mouth’.

He understands Lady Castlemaine’s patching in the same way, as being something between fashion statement and skin breakout – or maybe it’s more accurate to say that he sees it as a little of both. At the theatre, Pepys notes that this most public of figures – infamous mistress of Charles II – calls to one of her ladies ‘for a little patch off of her face’. Lady Castlemaine then ‘put it into her mouth and wetted it and so clapped it upon her own by the side of her mouth, I suppose she feeling a pimple rising there’. This is also fascinating for showing us a make-up running repair 1660s style: in the absence of mastic or gum, Barbara Villiers, Lady Castlemaine, fixes the patch with spit. But Pepys also writes more straightforwardly of the purely stylish flutter into patch-wearing on the part of Elizabeth, his wife. He thinks her handsome and pretty.4

Like most fashions, the wearing of patches came in for a good deal of criticism. As a purely decorative, self-enhancing practice of no utility or sense, it played into the hands of moral commentators who easily wielded the traditional weapons of attack. Patches were vain and irrational; they spoilt the pure beauty of God’s natural creation; they deceitfully hid the face, and in covering the truth were snares to catch the unwary in the toils of sex and sin. Unusually for such moral objection, however, this moment in English history offered an unparalleled opportunity to do something other than just complain. In June 1650, not long into the Puritan rule that followed the English Civil War, a bill was introduced into Parliament ‘against the Vice of Painting, and wearing black Patches, and immodest Dresses of Women’. But it was a fleeting appearance only. Unlike other causes of moral reformation – acts against blasphemous swearing, gambling, and stage plays – the bill against make-up and patching was immediately dropped and with no recorded discussion. Ever since the 1604 repeal of the acts of apparel – known as sumptuary laws, which legislated personal wardrobes on the basis of personal status and income – each attempt at introducing new laws had foundered on Parliament’s inability to agree on the pragmatics.5 It seems that even for a godly government intent on an ethical clean sweep, the regulation of personal appearance was a step too far.

But as a target for moral attack in everything from sermons to satire, patching had an added bonus. Its relationship to medical practice was an open goal for those on the offensive. Since plasters and patches were used in diseased and unhealthy bodies, it was easy to transfer ideas of illness and suppurating flesh to their wearers of fashion. And from there it was easy to assert a moral resonance between what was happening in the body and what was going on in the soul: patches were facial signs of spiritual spotting. The ultimate expression, which wrapped all these ideas together, was the sense that patches covered the sores and ulcers of syphilis. Voilà, patches became a written, and especially pictorial, way of representing a whore.

The patched prostitute is a long-running trope. It appears endlessly, for instance, in William Hogarth’s work of the mid-eighteenth century, where invariably the slide from innocence to moral – sexual – depravity is charted by the appearance of patches on a character’s face.

Look Closer…

This is the first of six plates depicting young M. (Moll or Mary) Hackabout’s descent into prostitution. Here, along with other young girls, she has newly arrived in London, just off the stagecoach from York.

The contrast between Hackabout and the old, heavily patched bawd is the visual focus of the scene. The rose in Hackabout’s décolletage and the sewing kit dangling from her belt indicate that she is a ‘country rose’ dedicated to womanly pursuits.

The patches on the old bawd’s face are uneven in placement and size, suggesting that they conceal blemishes – probably from venereal disease. Hogarth humorously compares the bawd’s facial patches to the polka dot fabric of her cape: both are numerous.

Look Closer…

Here Hackabout is transformed from a naive and innocent country girl into the cunning mistress of a rich Jewish banker, whom she distracts from the clandestine exit of her lover in the background by pushing over a tea tray. Her dress seems to be as loosely worn as her lost virtue, of which the big patch on her forehead is another visible sign.

This idea runs deep, a stereotyped commonplace that pops up here and there in different media, in different genres, and in wildly different linguistic and emotional registers. It’s found, for instance, embedded in this comic ballad from 1691, ‘The City Cheat discovered: OR, A New Coffe-house Song’. The song is cast as a humorous warning to young men on the perils of frequenting the capital’s coffee houses: it’s nothing but fake news, pickpockets, and prostitutes. And guess what, these women are powdered and patched (verse 4).

Listen to the song

Interestingly in Hogarth’s case, he leant heavily on the patching-equals-prostitution motif despite having elsewhere neutrally analysed the practice as a cosmetic enhancement. Ladies ‘of the best taste’, he had written, do not follow a rigid, symmetrical formality in dressing, but ‘choose the irregular as the more engaging’. He explains further. ‘For example, no two patches are ever chosen of the same size, or placed at the same height; nor a single one in the middle of a feature, unless’ – Hogarth adds – ‘it be to hide a blemish’.6

So Hogarth conjures three different nuances to patching. Like believing six impossible things before breakfast, Hogarth – and presumably many, if not most of his contemporaries – saw the patch as morally dubious, as an enhancement to beauty, and, like a particularly heavy concealer, as a solution to problem skin. As always with judgements on dress, context is everything: it depends on who is wearing it and where.

Patches were not necessarily confined to round spots. Commentary makes mileage out of the fanciful shapes they could take, describing faces pasted with stars, crescents and hearts. This is supported by rare surviving object evidence which has found its way into the collection of the Science Museum in London. Note though that the status and provenance of these patches is unknown. At some point in the late 1800s or in the early part of the last century, they seem to have been grouped together with other items: a display case of cosmetic curiosities from history. Were these things typical of their time, or did they survive for the very opposite reason, because of their weirdness?

Look Closer…

These black patches are glued to a light-coloured leather base, possibly for easier storage and application, or for display in a shop, or later collection as a novelty.

One thing is certain though. The more inflated claims of satire and censure need to be taken with not so much a pinch of salt as an artery-hardening shovelful. One frequently repeated theme concerns the coach and horses that some fashionistas had galloping over their cheeks or brow.

Our long-running belief in the literal truth of this seems to have originated with a book from the mid-sixteenth century, Anthropometamorphosis: Man Transform’d. Written by a man called John Bulwer, it’s an early work of comparative anthropology combined with large doses of criticism and social comment. Leafing through its entertaining pages, the reader takes a tour of the peoples of the world and all the weird and wacky ways they alter their appearances. It proved highly popular, and the original edition of 1650 was quickly expanded and illustrated.

Of patches, Bulwer notes that ‘Our Ladies here have lately entertained a vaine Custome of spotting their Faces, out of an affectation of a Mole to set off their beauty.’ Some, he says, ‘fill their Visages full of them, varied into all manner of shapes and figures’.7

This is accompanied by a woodcut of a woman whose face is liberally covered, including with the coach-and-horses patch. To underline Bulwer’s point further – to show that patching is a practice borrowed from ‘Barbarous Nations’ – the English woman is mirrored by a dark-skinned figure patched white on black. And if the reader is still unclear as to how they should interpret this body modification, next come eleven closely written pages censuring cosmetics of all kinds.

An urban myth, the coach-and-horses patch has, in writing and image, been repeated throughout the centuries and has now driven its way through the internet. Its truth, however, remains an exaggerated woodcut from nearly 400 years ago.

There is, however, an extraordinary new chapter in this story. Recently, a mid-seventeenth-century painting by an unknown hand came up for auction in a small English town near the Welsh border. It depicts exactly the same scene as the Anthropometamorphosis woodcut, but mirrored in reverse. The similarity is too striking to be accidental.

We think it most likely that the provincial artist used the book as his – or very possibly her – inspiration; a template for an artistic and moral exercise combined. The European woman is rendered more competently than the black-skinned figure; the one drawn from life or from a painted exemplar, the other an imagined extrapolation from the woodcut. It’s clear that the artist was not familiar with different ethnic appearances. If you look closely at the shape of the black woman’s nose, for instance, it resembles not real life but the illustration in the book. The moral take-home of the exercise is painted in a phrase at the top – physically hard to read but all too easy to comprehend: ‘I black with white bespott y white with blacke this evil proceeds from thy proud hart then take her: Devill’.

However, maybe the critiques haven’t worked? Maybe you’ve not been dissuaded from patches? If you should happen to find yourself wandering the streets of Restoration London and desirous of purchasing some, the writer Hannah Woolley gives us a clue as to where you should go. For in her conduct manual – a guide to morals and behaviour – she disdained both the ‘Beautyspots’ themselves, and those boutiques that ‘are furnished with a daily supply and variety’ of them.8 So, make your way either to the New Exchange or the Royal Exchange, double-height galleries full of the loveliest shops selling the most desirable of fashionable must-haves. Or maybe go to Westminster Hall, the third of London’s most delicious shopping precincts.

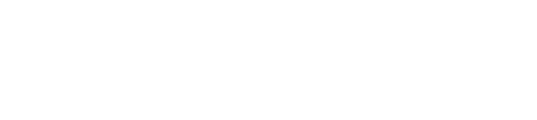

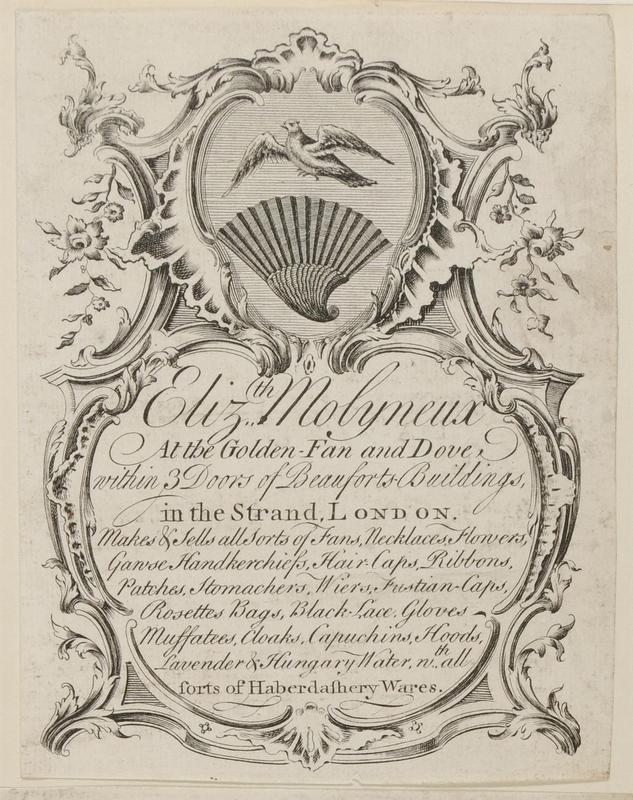

Almost certainly, it was from one of these places that Elizabeth Pepys bought her patches. By the eighteenth century we have named sellers, haberdashers like Elizabeth Molyneux and Isaac Rimington, whose wonderful trade cards advertise their abundant and enticing wares. Elizabeth, whose shop was near the Strand, suggests that the patches she sold may have been made on the premises

But what of men? Contrary to common belief, in England the male wearing of fashionable patches was rare. For a culture increasingly moving away from overt masculine display and turning instead towards tailored restraint, patches were seen as too effeminate and affected.

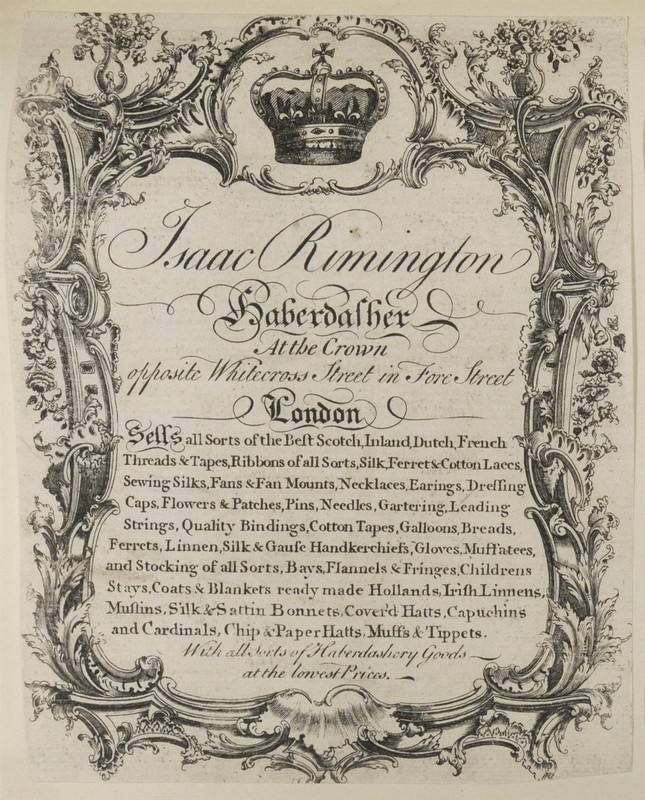

Even in satire, male patching is uncommon, and when it does appear is usually the sign of a fop. Look, for instance, at the absurd figure, the Macaroni, one of the many comic prints published in the 1770s. Everything is exaggerated to make the point: spindle legs, a sprigged and spotted suit, the vast nosegay and even vaster wig, the tassels and frogging, the ribbons and the patches. This simpering figure shows male beauty spots to be the reverse of the battle scar that was patched as a badge of honour.

And anyway, by the time this was created, patching in England was long past its heyday of the early eighteenth century. The black spots in these late satirical prints are not a reference to current trends but are instead symbolic – a way of picturing ridicule and criticism of a range of appearances and behaviours in both men and women.

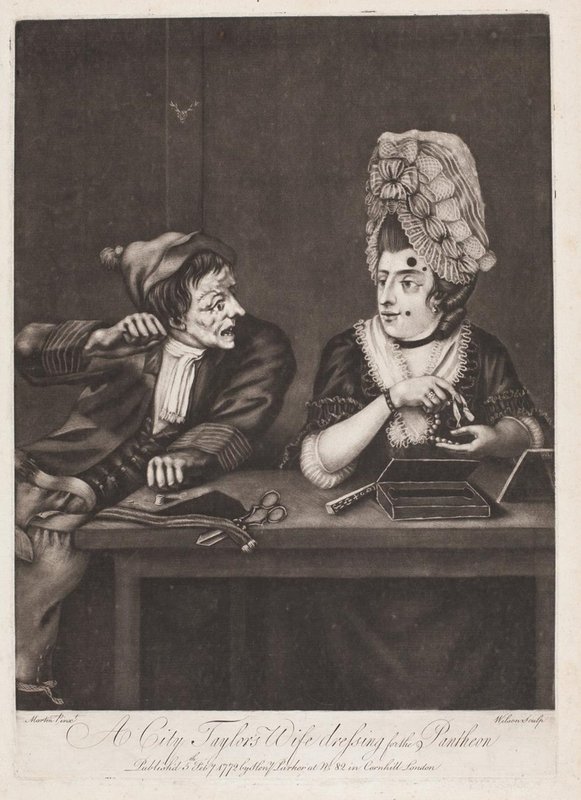

We can see this in A city taylor’s wife dressing for the Pantheon of 1772. The Pantheon was the newest of London’s venues of entertainment, opened that very year for concerts, assemblies, and masked balls. Unlike more exclusive venues, admission was by ticket alone, meaning that all sorts could, and did, mix within. In the print, the gaunt tailor remonstrates with his wife, who is dressed both above their means and their station. The antlers on the wall above his head – cuckold’s horns – suggest the sort of entertainment for the night that she has in mind.

Our last image picks up on the theme of masking and masquerade, hinting at an idea that began to emerge and eventually was to overtake the patch as a sign of the prostitute. With time, patches began more neutrally to connote ‘dressing up’ – the playful putting on of a character, the fun of artifice, and nostalgia for an imagined past.

So much for patches.

But what of the patch box?