Once there were patches, people needed somewhere to keep them.

Enter, eventually, the patch box.

Look Closer…

Philippe Mercier, a German-born painter and engraver of French Protestant extraction who spent most of his career in England, specialised in French-style genre paintings.

This image is akin to Mercier’s other depictions of young girls occupied with domestic pursuits. Most of these paintings were produced to be later engraved. The limited brown palette of this image may indicate that it had been intended to be copied into the black/white medium of engraving.

The patch box here closely resembles the little round tortoiseshell and mother-of-pearl containers popular during this time. Although Mercier re-works here a French visual formula, the subject of patching is toned down in comparison. This was probably in response to the tastes of an English rather than French audience.

Take a look at this short scene adapted from The Lying Lover: or, The Ladies Friendship, a 1704 comedy by Richard Steele.

Wonderfully, it features an early cameo appearance of the patch box. Penelope and Victoria, the two ladies, are vying jealously with one another, the exaggerated politeness of each hiding a determination to make her friend look less attractive. Both of the women take up a box and use its contents to patch her rival as badly as she can, before they together sally forth to meet Bookwit, the young man.

Crafted into an inventive array of shapes and designs, one thing that all patch boxes had in common was their diminutive size. All were small enough to be held in the palm. Some sat on dressing tables but others travelled in pockets. Their dimensions, incidentally, definitely circumscribe the size of anything that fits inside. In other words, patch boxes deflate the exaggerations of satire, and suggest that patches were of modest proportions.

The earliest of the surviving boxes seem to date from the end of the 1600s – so the best part of a century after patches first begin to be talked of as a possible fashion. The earliest mention of them that the Oxford English Dictionary can find is 1673, still decades after cosmetic patching makes the mainstream.

Mostly made of luxury materials – silver, gold, mother-of-pearl, tortoiseshell – the boxes were a small manifestation of vast commodity networks. These were global materials, desired, bought, sold and shipped the length and breadth of the known world.

Curator’s Notes: ‘Materials and Miniaturisation’

Look Closer…

This patch box was acquired by Queen Mary, consort to George V and grandmother to Her Majesty, Queen Elizabeth II. The box was probably made by artisans in Paris or Dresden specialising in small containers of semi-precious stones richly covered in gold cagework. This box is made of amazonite, an opaque, semi-translucent mineral of turquoise colouring that was imported from Africa, India, Brazil and Australia. Agate, equally favoured for its semi-translucency, was another popular gemstone used throughout the eighteenth century for little boxes like this. The hexagonal form is unusual and may point to it being a late nineteenth-century copy inspired by eighteenth-century craftmanship. This little box, however, not only enchanted its owner with its rich colouring and contrast of luminous turquoise and glimmering gold, but also the musical theme of its decoration: the putto on the lid sits atop a pile of instruments while playing the flute.

Look Closer…

This patch box was designed and manufactured for Queen Mary II, who co-reigned with her husband, William III, from 1689 until her premature death in 1694, aged just 32.

Probably, a continental jeweller working in London manufactured it for the Queen during the last year of her life. Her crowned monograph is set in deep red enamel, the colour of royalty, and surrounded by a floral border. This floral motif continues around the side of the box.

The design is fitting for a Queen with a passion for flowers and horticulture. Mary was an avid collector of plants and, together with William, created the spectacular Great Fountain Garden at Hampton Court Palace.

Consider tortoiseshell

Surrounded by plastic imitation, it’s easy to take tortoiseshell for granted, so much so that now it conjures a pattern and colouration rather than the actual creature – the hawksbill turtle – from which it was stripped.

While the supply from South-East Asia was dominated by the Chinese, most British tortoiseshell came from the West Indies – yet another fruit of Britain’s increasingly large colonial harvest. Because the hawksbill turtle was a solitary creature, it could only be hunted singly and traded as a luxury side-line to the bulk of reliable main commodities. This kept it as an exotic luxury, but also prompted the development of imitation products.

Long before plastics gave us faux tortoiseshell, there were eighteenth-century imitations made by treating ordinary old cattle horn with quicklime and lead, mottling it into pretty fakes. (Despite this, the hunt for the real thing continued and, over the subsequent centuries, grew ever larger. Trade in the species was banned internationally in 1977; forty years later, the hawksbill remains on the critically endangered red list.)

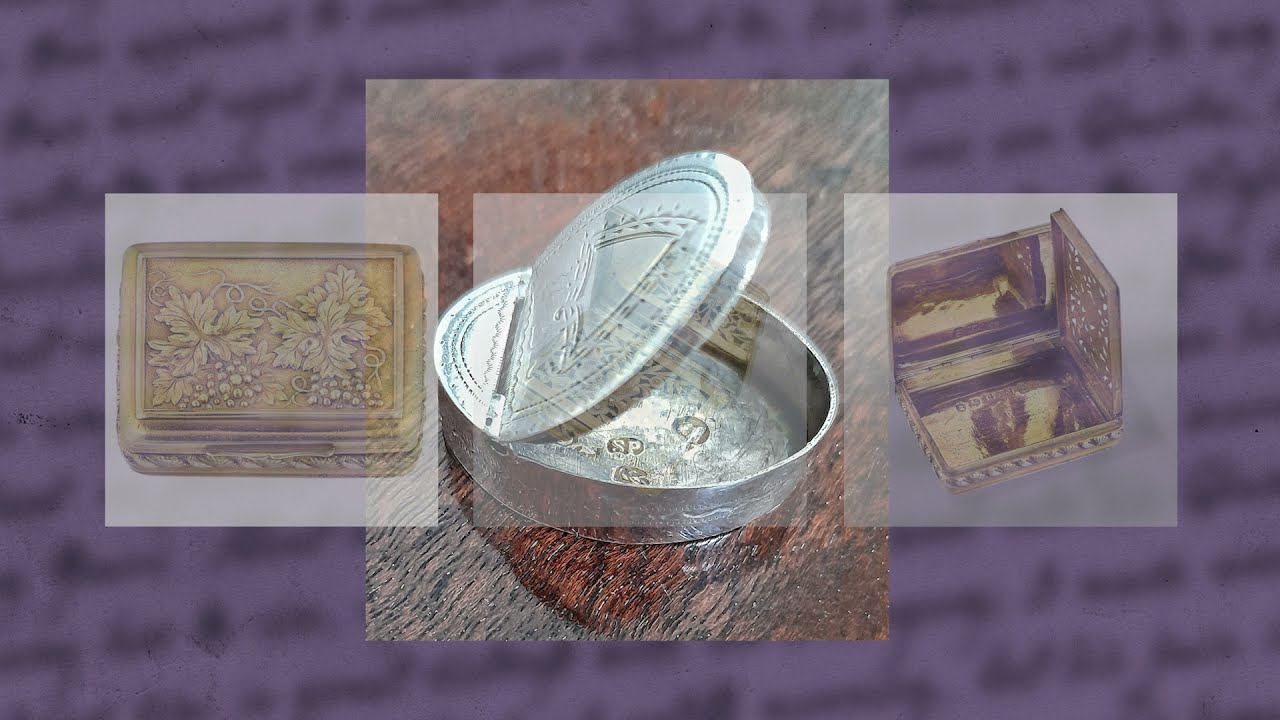

Both faux and real tortoiseshell patch boxes were further embellished with piqué work – small inlays and dots of mother-of-pearl, silver or gold. But despite the exoticism and preciousness of these materials, patch boxes were only small and many were therefore affordable luxuries.

Not for the literal or metaphorical pockets of the majority, sure, but able to be bought by the genteel. And for those on the social rung below, cheaper options – like this patch box below, silver-plated in Sheffield – made for charming trinkets on a budget.

Anyone fancying a patch box could purchase one from the usual places that decorative fancies were made and traded, like silversmiths, goldsmiths, and jewellers. You could also go to someone engaged in the ‘toy trade’. These were not sellers and makers of items for children but playthings for adults: pretty, fanciful objects where decoration was placed above function. The items may have had a use, but this was merely the vehicle for their ornament.

Curator’s Notes: ‘Mock Turtle’

Mr Deard, his business in the desirable shopping precinct of Westminster Hall, was a seller of such ‘toys’ in the 1720s.

His list of wares was exhaustive: boxes of all sorts – including for patches – in gold, silver, amber, agate, shell and tortoiseshell, you name it; engraved, set with diamonds, rimmed with gold, variously made to glitter and delight. He sold elaborate buckles – for shoes, for garters, for girdles, for men, for women.

There were seals for documents (useful), which were decorated with diamonds or gold (unnecessary); a dubiously functional pair of silver padlocks; and an entirely functionless set of amber eggs with gold rims. Though, to be fair, the eggs probably opened along these rims, making them into whimsical containers – a special subset of boxes in their own right.

Trifles like this were elegant. They were also easy to steal. So, amongst other things, patch boxes therefore crop up here and there in court proceedings and notices of theft.

In January 1700, for instance, the house belonging to George Heneage, Esquire in London was looted in a fire. Along with jewellery, clothing, and plate was stolen ‘a Cover of a silver Patch-Box’.

Look Closer…

The elegant figures gracing this tiny patch box are hand-painted on hard-paste porcelain, the first kind of porcelain produced in Europe. The German alchemist Johann Friedrich Böttger discovered its secret in 1708. In 1710, the Meissen porcelain manufactory opened near Dresden, under the patronage of August the Strong, King of Poland and Elector of Saxony.

This little egg-shaped patch box shows that even as a royal factory, Meissen designers eagerly sought to keep abreast of trends, with novelty products as wide-ranging as thimble and watch cases and bonbonnières. This patch box was produced about a decade before Meissen’s monopoly of hard-paste porcelain manufacture was broken by the royal French factory in Sèvres.

The owner of this patch box may not only have appreciated handling the smooth, cool surface, but also delighted in the scenes of dalliance. Patching was, after all, meant to raise one’s stakes in the game of flirtation and attraction. Observe the cooing doves depicted next to a forthright gentleman fondling his lady’s breasts. Below, a conversing couple stands next to a girl with an empty cage (watch The Curator’s Note video ‘What is in a Cage?’ in Room 6 to learn more about the symbolism of the cage).

In January 1700, for instance, the house belonging to George Heneage, Esquire in London was looted in a fire. Along with jewellery, clothing, and plate was stolen ‘a Cover of a silver Patch-Box’.

The records of the Old Bailey, London’s chief criminal court, are another source. In 1722 two shoplifters, James Lanman and Robert Drumman, were sentenced to death for pilfering, among other things, three patch boxes made of mother-of-pearl.

A woman and man in 1761 were found guilty of, respectively, stealing and receiving. Among the items for which he was sentenced to transportation and she to be hanged, were twelve plated patch boxes, value 20 shillings; six ‘pebble’ patch boxes, set in silver, value £1, 4 shillings; and one paper (papier mâché) patch box, value 1 shilling.

Around nine at night on 11 June 1719, a lady took a hackney coach from outside the General Post Office on Lombard Street.

In between there and being set down at her destination she lost her pocket. Bear in mind that at this date women’s pockets were separate ‘garments’, worn under the skirt and tied on round the waist.

In company with her pocket, of course, the lady in question lost its contents – desperately annoying for her, but for us a most wonderful glimpse into the past.

Along with unfortunately unnamed ‘other Things’, was a toothpick case, a small bottle with a gilt stop, a bunch of four keys, and ‘a Tortoishell Patch-box, with a Looking glass on the Inside thereof’. The lady offered a two-guinea reward to get her belongings back – or, since they ‘can be of no use but to the Owner’, one guinea for the bunch of keys alone.

The point is that patch boxes were pretty, many were pricey, and all were eminently portable. Easily lost, found, stolen, and resold, in the eighteenth century a patch box could pass through many hands and circulate in ways both legitimate and more clandestine.

They also formed a class of object with similar containers, whether for snuff, for sweets, for trinkets, for toothpicks, for pleasure, for collecting, or for giving to someone else. As the ‘egg shaped box’ above suggests, their variations were all but endless.

Look Closer…

The mid-eighteenth century saw a vogue for figural scent and cosmetic containers. Specifically, smaller and innovative porcelain manufacturers, such as the Chelsea factory in London, specialised in novelty products such as funny and rare multi-compartment cosmetic containers.

The Chelsea factory was established by Charles Gouyn and Nicolas Sprimont in 1743 and worked with soft-paste porcelain. Scent bottles in the form of human figurines, exotic birds, cats and dogs often combined with a patch box were a speciality (see the lovely examples in the Museum of London and the Gardiner Museum of Toronto).

Six years later, Gouyn withdrew after a change in proprietorship and this humorous little patch box was probably produced in the break-away factory Gouyn operated just a mile away.

Let’s face it, boxes were big in the eighteenth century. It seems the market could not get enough of those dinky little devices for putting things in. And because of this, it can be difficult – often impossible – to tell them apart. Even for museum specialists these containers can be a cipher. Their dating is also often at best only approximate. In fact, the more we find out about patch boxes, the less certain they become.

If a patch box is not used for patches, is it still a patch box?