Around 1910, something very curious happened: starting in Paris, patches and boxes to keep them in made a comeback.

The pages of American Vogue explain:

The newer, most fascinating of all the little accessories of a fashionable woman’s toilette, a little patch box holding the ‘pattes de mouche’ which have returned to favor with other adorable fancies of the 17th and 18th centuries. Happy she who owns one of these treasures handed down to her from some beautiful ancestress! Other less fortunate women ardently search the shops of the antiquaries along the quays, or in dark narrow streets of the Latin Quarter, for these tiny bibelots carved in gold, ivory, and enamelled, that served the beauties of two hundred years ago.

The article goes on to give this fashion from the past a particular slant for today by linking it with the new mirrored powder compact, which was itself facilitating a huge shift in public behaviour. For it enabled women to do a novel, daring, and by no means universally approved thing: not only wear makeup, but unashamedly own up to it by applying it in public. Patching, the magazine suggests, can be performed by the modern ‘coquette’ with the same daredevil élan. She is to use ‘black plaster cut in rounds and ovals; and she sits as serenely in a public restaurant or tea room adjusting a loosened bit, as when she powders her dainty nose’.1

In the very next issue Vogue followed up with an article about Parisian shopping, showing that even if you can’t find ‘the real article in the antique shops’, you can at least for nine francs buy a new ‘tiny square patch box’ of silvered metal: ‘old in idea, but quite modern in make’. They will ‘store the tiny bits of black plaster used now, as of old, to heighten the delicacy of the complexion’.2

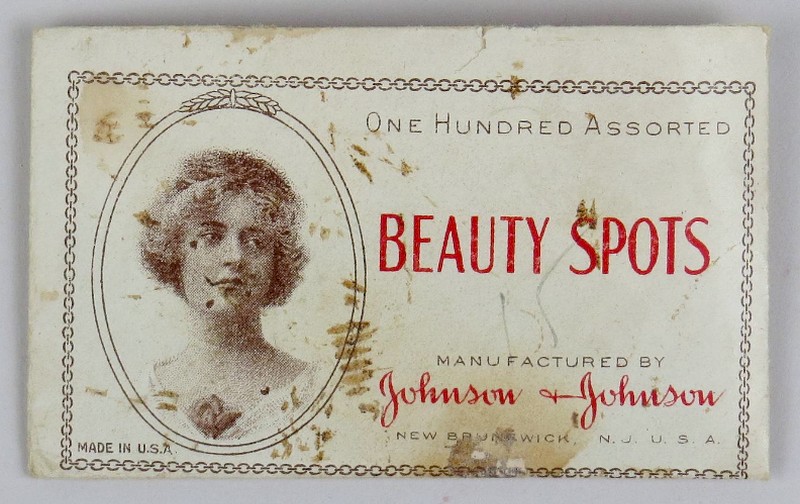

We can see an example of these ‘tiny bits of black plaster’ that Vogue was promoting, for by 1915 Johnson & Johnson had scented an opportunity. Using left-over material from making regular surgical plasters they developed a side line in facial stickers – echoing, in fact, the original migration of the patch in the early seventeenth century.

The company’s trade journal explained the product to the retail druggists in whose shops the public would buy them:

To supply the demand created by this fashion we have arranged an assortment of designs consisting of stars, crescents, arrow points, hearts, etc., which are put up in envelopes, each containing 100 spots (3 dozen on a card); also in fancy boxes containing 300 assorted.3

In the years that followed, the patch – or beauty spot as it was now known – had some high-profile wearers, like the film icon Clara Bow, or the British actress Benita Hume.

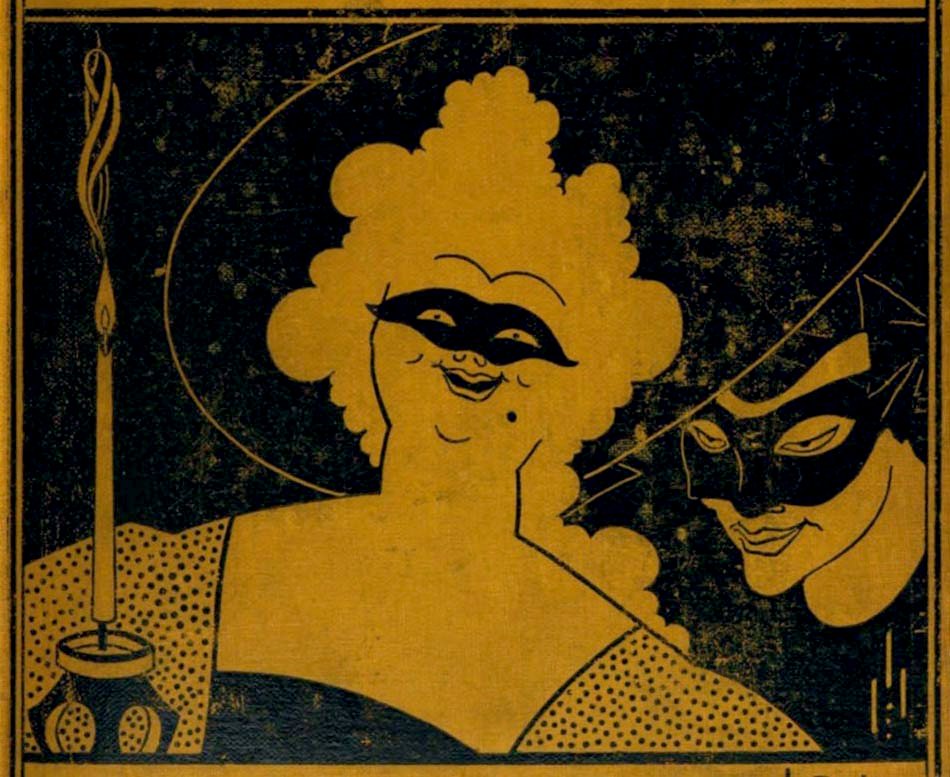

But there is something very self-conscious about these revivals and reappearances. They seem more like consciously created fads than genuinely widespread trends. Playful but perfunctory; fun but fleeting.

In fact, we see here the afterlife of patching: not a new style but a knowing one; not fashion but ‘dressing up’. Patches and dots become a way of doing masquerade.

This move on the part of patching from being unthinkingly in the here and now, to gesturing knowingly at the there and then, suggests one final point. The way the patch and its box have shaped – and continue to shape – our image of the past.