Question: What do you give as a present at a late-Victorian society wedding?

Answer: An antique silver patch box.

We all know about that strange cycle that turns the outrageous into cutting edge, cutting edge into mainstream, mainstream into fuddy-duddy, and fuddy-duddy into desirable. By 1890 the high-end, luxury patch boxes from the earlier part of the eighteenth century were drawing a new admiration from those who knew their taste to be good.

On the very first day of the decade, Myra’s Journal, a periodical for ladies, featured an article on ‘Artistic Homes; or Fashion in Furniture’. It waxes most eloquently on the charm of beautiful mementoes from history. It even illustrates a new kind of ‘show table’, glass-topped with a sealed-in velvet shelf below, on which can safely rest valuable ‘souvenirs of past times’: ‘a snuff box recalls the time of the Regency, and a patch box takes us still further back’.1

.

Look Closer…

This little patch box is not merely a container, but also a portable calendar. The two sides of the box have rotating dials. This trefoil form also gives access to the three little compartments.

The owner could move the upper dial so that the weekdays matched with the date. The traditional planetary symbols – for the Moon, Mercury, Venus, the Sun, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn – are used as decoration. The dial underneath calculates the hour of sunrise and sunset and the duration of the days and nights.

Perpetual calendars integrated into miniature silver items like this were German novelty products made for the eighteenth-century luxury market. However, the calendarium perpetuum was not a new, but a very old form of timekeeping that was already widespread in late fifteenth-century Germany in the form of single-leaf printed papers. Specialised religious and agricultural calendars, marking things like feast days and gardening tasks, were in use throughout the sixteenth century and beyond.

Again, the term ‘patch box’ is deceptive. This little box could store any tiny item. It may well have been a pill box that even prompted its owner to take a regular dosage.

The published lists of wedding presents given to society couples at the time, which stretch down the columns of newspapers and magazines, likewise contain more than a smattering of these kinds of antique gold and silver objects.

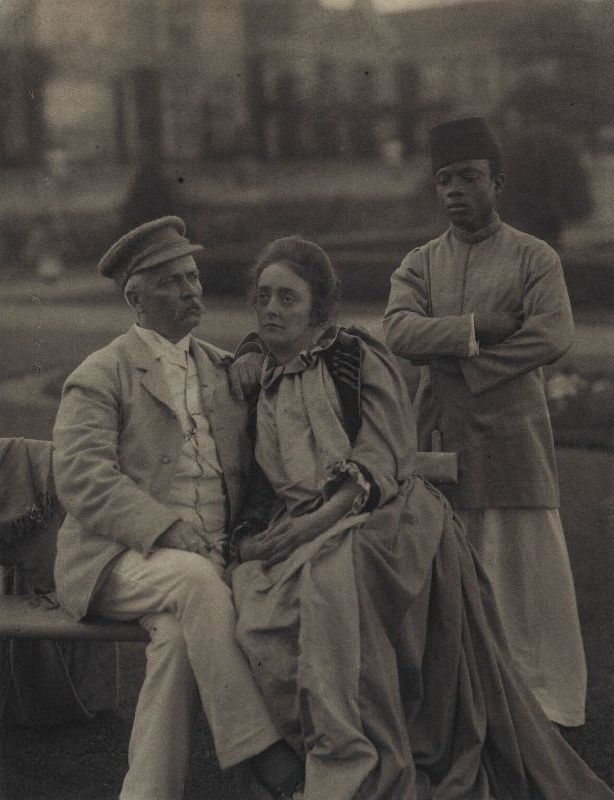

The marriage of the famous explorer Henry Stanley – ‘finder’ of Dr Livingstone – to Dorothy Tennant was big news. Westminster Abbey was full of everyone who was anyone, starting with Prime Minister Gladstone and working on down. Hours before, crowds began to mass outside the doors. There was bunting on buildings and costermongers selling accounts of Stanley’s adventurous life. The largesse of presents – from royalty, both British and foreign; from colonial companies and American politicians; from English aristocrats and royal academicians – was displayed at the reception and described in the Times. The glare from the silver alone must have been enough to induce migraines. And doing its modest part to add to this glinting lustre was one ‘antique silver patch-box’, given by one Mrs Francis Parker

by Eveleen Myers (née Tennant), platinum print, 1890, NPG Ax68770. Photo: © National Portrait Gallery, London, reproduced under CC BY-NC-ND 3.0.

By the end of the nineteenth century, people of taste, it seems, could never fail to be charmed by ‘some trifle of a tiny patch-box in wrought silver’.3 There are even signs that those with more modest incomes could enjoy the collectability of the very much cheaper enamel patch boxes. If you didn’t happen to have ‘the little silver bibelôts all modish women seem to possess nowadays’, you could get a dainty curio-table to properly display those ‘miniatures, enamel patch-boxes, [and] old seals’ that lie here and there about the house.4

So, just when it seemed as though the patch box would sink without a trace, the reports of its death turned out to be much exaggerated. Indeed, the box and its patch were on the cusp of a revival.