Patch boxes from the second half of the eighteenth century were mass produced, but they also had mass appeal.

They are delightful, infinitely collectable, and reference almost every area of contemporary life. With little practical function, enamelled patch boxes of this period are primarily carriers of a design. They are small portals to a set of emotions, beliefs and memories.

Let’s look at the typical types of decoration.

Many have bold colour schemes, particularly on the sides – solid blocks of blue, pink or green particularly. The design on the lid is often encircled by raised white spots, like pretend seed pearls.

Elements also echo other genres, such as miniatures painted in enamels, also popular at the time. But there is much, much more to what you can put on the lid of a patch box.

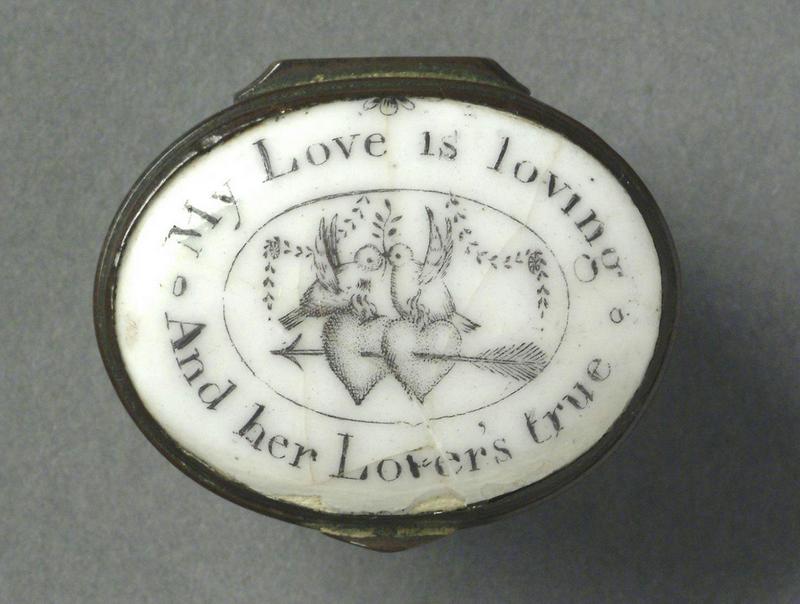

Like greeting cards today, boxes with sentimental mottos were a paradox: made in bulk for a one-off occasion; mass-produced for a unique use.

Making a consumerist market out of relationships – using an industrialised template to pattern individual experience – suddenly makes these boxes, despite their age, seem very modern. There is a sense in which they could be said to be teaching the expression of particular kinds of feelings – doing their bit to form the events in which they appeared.

Let’s think about this in today’s terms. Why do we give cards on birthdays? Would Mother’s Day and Father’s Day be celebrated in the same way without their commercial paraphernalia? How many people buy ‘best teacher’ cards at the end of the school year who might not otherwise have thought to express a formal ‘thank you’?

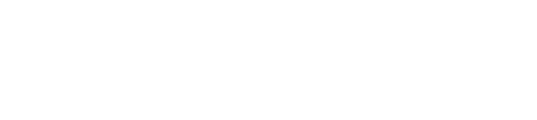

Some of these verses present as tokens of courtship.

A few look rather saucy.

Curator’s Notes: ‘What Is in a Cage?’

Patch boxes frequently play with the idea of the mirror under the lid that will reflect the viewer back to themselves.

Look Closer…

The verse on this patch box is typical of contemporary popular literature – the sort that offered its readers the light entertainment of short stories, sonnets and intriguing snippets.

This verse comes from a small poem that circulated, in both its French and English versions, on both sides of the Atlantic. In 1827, for instance, it was featured as a poem by ‘a man of gallantry’, which he wrote on his mistress’s mirror.1 Literature like this, particularly with themes of idealised romance and courtship, was aimed at a female readership.2

With its fashionable pink colour, reminiscent of the popular Rose de Pompadour first marketed by Sèvres in 1757, this box would have appealed to a fashionable young lady.

Curator’s Notes: ‘The Eyes Have It’

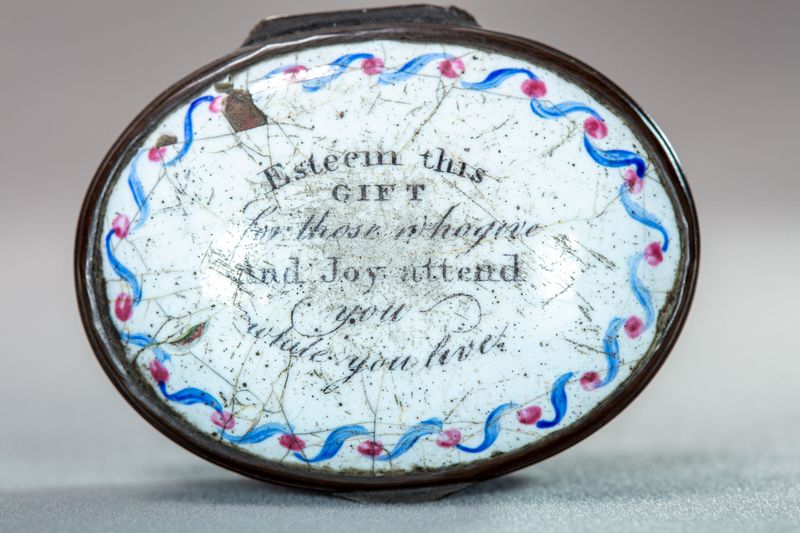

It is also clear that many, perhaps most, are pitched as gifts, whether from would-be lovers, from friends, or among family members.

Look Closer…

The decoration of this patch box imitates tiger cowrie, a species of mollusc (Cypraea tigris) native to the Indo-Pacific. Since ancient times, the creature’s large shells were valued for their vivid pattern of blueish, black, and red dots on a smooth, lustrous white ground. The French and British exploration of the Pacific during the eighteenth century enhanced trade routes to Europe, and along these routes flowed many desirable and exotic commodities, including the tiger cowrie. Shells became widely available and affordable.3

Our patch box is probably inspired by the highly popular metal-mounted cowrie shell snuff boxes that were produced in specialised workshops across England and of which you can see an example from the Philadelphia Museum of Art. It therefore imitates something familiar, yet more expensive.

Ultimately, the imitation of naturalia with paint evokes the Humanist idea that art vies with, or even surpasses, nature. Does the patch box invite comparison of man-made and nature’s enamels? Or is this patch box just a piece of fakery to catch a mother’s eye?

A few of the boxes suggest mourning – or perhaps ‘memorialising’ might be a better way of putting it. ‘The Absent not Forgotten’, is one motto that recurs, along with imagery of urns and funerary-type monuments.

However, others are altogether more robust, pulling the rug from underneath the feet of any mawkishness. Look at this one slyly poking fun at relationships of mutual exploitation.

Some designs take dogs, cute emblems of fidelity, and curl them over a patch box lid. Though as so often, putting containers of this period into clear categories is problematic. Some of those here may in fact be bonbonnières, little boxes for sweetened cachous or lozenges. These three also have an extra decorative flourish on the base (or the lid, depending on which way they are approached).

A whole, endlessly repeated series of patch boxes catered to the new habit of tourism that developed at the time. Thanks to eighteenth-century improvements in transport – roads, carriages, toll routes, coaching services – people could go more places, faster. And with incomes and the middle classes on the up, there were more and more wanting to do so. Added to this, the new interest in places, scenery, and landscape – in the ‘picturesque’ as it was called – meant that travel for its own sake became the thing. And when you got to where you were going, you could buy a souvenir to take back home as a reminder for yourself or a gift for someone else. There are plenty of these for the tourist hotspots – spa towns like Harrogate, Bath and Buxton; cathedral cities like York and Lincoln; fashionable resorts like Brighton.

Look Closer…

The peak of the Bilston enamelling trade from 1760 to 1790 coincided with the burgeoning of domestic tourism in England. Improved road networks, cheaper coach services and communications made travelling easier and safer, and travel accounts and tourist guides shaped expectations of the experience. Patch boxes, with their vast choice of topographical motifs, must be understood within the mass production of tourist paraphernalia of the experience. Bilston delivered souvenirs to all major cities and places of interest in England, including Yorkshire’s spa town of Harrogate. We can relate to this: souvenirs of Europe’s cities are often produced in the Far East. Nevertheless, Bilston patch boxes perhaps contributed to the formulation of a national, architectural heritage and geography in people’s minds.4 This was spear-headed by the numerous travel descriptions of England published during this time that offered the aspiring tourist everything from notes on the details of buildings, to social history, to the quality of a town’s air and roads. Bilston engravers copied topographical views from these travel guides and from books of drawings. Both travel literature and Bilston patch boxes may have fostered a greater sense of heritage by making it accessible, replicable, and collectible.

Look Closer…

Today we are accustomed to appreciating the broken remnants of historical architecture and regard such remains as worthy of preservation. For the first owner of this patch box, this may have been a relatively new attitude to the past. This view of the ruins of Knaresborough Castle may have appealed to a tourist with a taste for the picturesque.

The picturesque was an aesthetic ideal that gained currency during the last three decades of the eighteenth century. It favoured the irregular, rugged and accidental as opposed to the smooth, symmetrical and proportionate of classically inspired artefacts. Wild scenery and ruins became valued as places of a new romantic beauty. They gave viewers the opportunity to contemplate the grandeur of nature and the past. The influential artist, cleric and travel writer, William Gilpin, even suggested that the classically inspired architecture that had been earlier admired – all columns and harmony – was not fit for depiction in art. We must first, he said, ‘beat down one half of it, deface the other, and throw the mutilated members around in heaps’. A truly artistic view needed not ‘a smooth building’. Instead, ‘we must turn it into a rough ruin’.5

While the mass-produced patch box is only tangential to these principles, it illustrates that such ideas had reached a general audience. The owner’s desire to visit this ruin and to purchase this keepsake may have been encouraged by them.

Look Closer…

A particular aspect of tourism in late Georgian England were spa and resort holidays. Spa towns such as Harrogate, Bath and Buxton in Derbyshire were top destinations for those in need of the curative qualities of thermal springs or desirous of the social scene they attracted.

Designed by John Carr of York and built in1780, Buxton Crescent housed what we would today call ‘boutique spa hotels’. Architecturally indebted to Bath’s Royal Crescent, completed only five years earlier, it established Buxton as a contender in England’s geography of rival spa towns. This patch box would have evoked the aura of luxury associated with Buxton’s new architectural landmark.

A royal watcher could visit Windsor and take home a patch box to complete the experience.

Look Closer…

Sometimes the subjects depicted on patch boxes give us clear pointers to their date of production. ‘The Queen’s Palace at Windsor’ thus poses the question: which queen is it? It’s unlikely that this fine patch box dates after Queen Victoria’s coronation in 1837. The Bilston enamel industry was by then defunct owing to a general economic decline, the subsequent rise of the coal and iron industries, and a new vogue for glass and metal trinkets. It is more likely therefore that this caption refers to Queen Charlotte (1744–1818), wife of ‘mad’ King George III.

Charlotte has a particular connection to Windsor, more precisely, to Frogmore House, a rural retreat she purchased in 1790. Besides enlarging and modernising Frogmore House, Charlotte later also ordered the building of Double Garden Cottage (subsequently ‘Frogmore Cottage’).

Frogmore estate became a much-loved retreat for the Queen and her eldest daughters specifically after the 1789 Regency Bill crisis prompted by the King’s worsening mental health. Charlotte was made guardian of the person of the King, his court, and all minor children. Her indelible association with the Frogmore Estate and her charge of the King’s person would have made Windsor Castle ‘The Queen’s Palace’.

More surprisingly, patch boxes were also made as souvenirs for tiny destinations whose tourist pull was modest and whose fame was only local. Here is a simple one that advertises Leyburn in the Yorkshire Dales.

Looking at patch boxes, you can’t help but get the feeling that their designers were casting about for a new angle – anything else, as long as it would sell another unit. Topical events were therefore hurried off the transfer paper and onto the lid.

The first box here commemorates the Battle of Camperdown, just one of the engagements in the French Revolutionary wars that sprawled across the nations and continent of Europe. This particular battle was fought between the British and the Dutch, and was a resounding victory for the Royal Navy. The script around the edges simply reads: ‘The Glorious 11th Oct 1797’. Patriotism in a patch box.

But when someone has hit on a good scene it’s a pity to waste it on a single event. That’s why the next patch box is almost identical, even though it commemorates a different conflict entirely, the Battle of the Nile of 1798.

The Battle of the Nile was the engagement in which Lord Nelson defeated the French navy and, in the process, was raised to the pantheon of British heroes. Although it reuses an earlier motif, it’s just one example of a whole genre devoted to his exploits. This did not stop with his death at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. Rather, a whole new range of designs was then produced in his honour, which combined stirring patriotism with post-mortem remembrance.

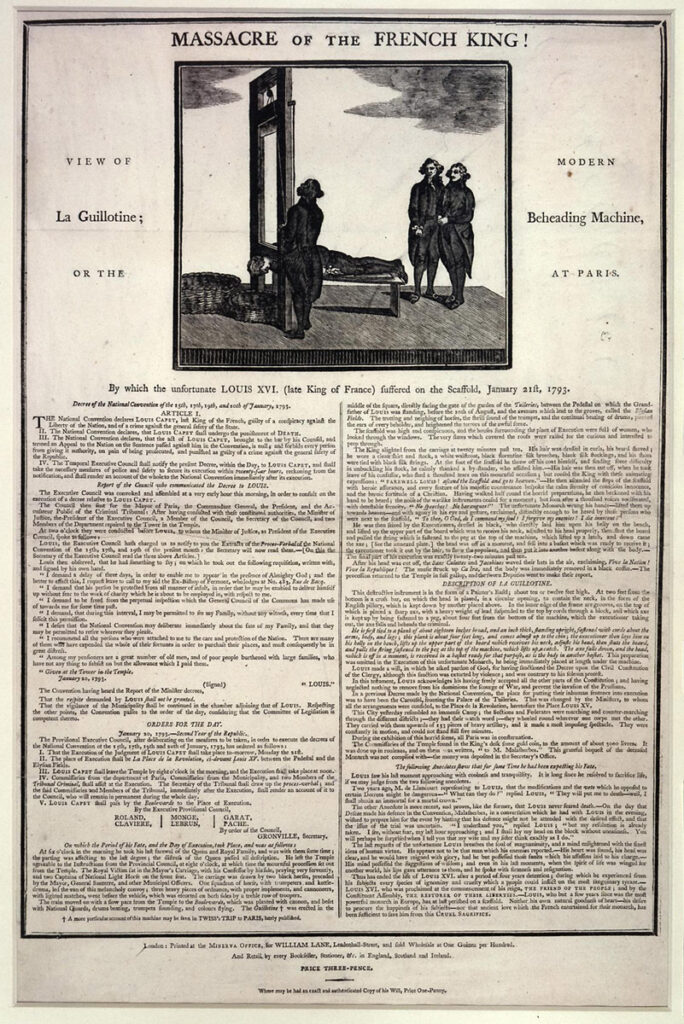

The most striking example of a topical event has to be a box from c.1793, held in the collection of the British Museum. It commemorates the execution of the French king Louis XVI, framed with the motto ‘He Died Lamented by all Good Men’. While the Wolverhampton Art Gallery has a 1770 patch box depicting a rather porcine and louche-looking Louis of two decades earlier, the British Museum box illustrates the very moment of his death. In the middle of the lid is the guillotine with Louis’s body. His head is in the very process of rolling off, perpetually enamelled in motion halfway between his shoulders and the waiting basket below.

We are lucky enough to also have the source from which the engraver drew his inspiration for this, an illustrated broadside (a single-sheet format) on the French king’s trial and death. The direct relationship between them is evidence for the way that the engravers of transfer prints were free to draw on any material that took their fancy as a commercially viable proposition.

The discovery of an identical design transfer-printed onto other items shows our patch box fitting into a wider world of merchandise, one in which profit and propaganda cosied up together in a mutually beneficial partnership.

![A basket sits under a guillotine ready to receive the head that is about to fall., and the words, 'View of [La Guillotine] or the [modern beheading] machine [at Paris by which] Louis XVI [late king of] France [suffered] on the [Scaffold] Jan 21 [1993]'](https://dmda.york.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/patches-06-29a.jpg)

![Three men stand around a guillotine with a decapitated man lying tied to it and the words, '[View of] La Guillotine [or the] modern beheading [machine]. at Paris by which [Louis XVI] late king of [France]suffered [on the Scaffold [Jan 21] 1993'](https://dmda.york.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/patches-06-29b.jpg)

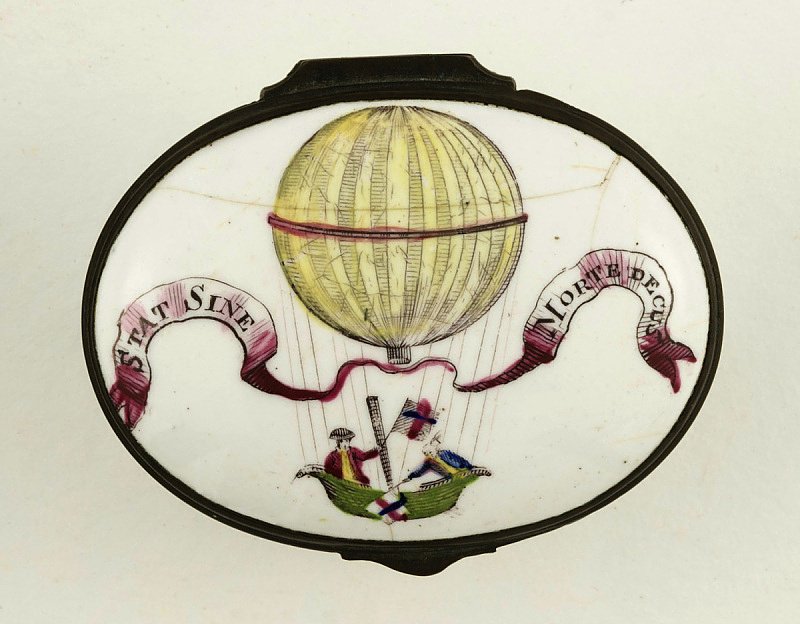

The new and exciting world of aeronautics was another topical theme. After Lunardi’s first flight in 1784, ‘balloonomania’ hit.6 Balloons were the subject of the moment, featured in everything from science to satire, fiction to fashion. Ascensions became huge spectacles – public entertainment events – and what better than to buy a patch box to mark the occasion.

But the subjects canvassed on a small enamelled lid could also be far more serious. An inhumane institution, but one whose profits had made Britain very rich, was coming under intense scrutiny. While plantation owners and business interests lobbied for the continuation of slavery, abolitionists found a range of ways to spread their message. And one of those, unlikely as it might seem, was the patch box.

This design likely originated with medallions created by Josiah Wedgwood in 1787. Featuring a figure in chains encircled by the phrase ‘Am I Not a Man and a Brother’, the medallions were shared widely and gave a visual coherence to the abolitionist movement. The motto became a catch-cry and its motifs appeared on a range of merchandise, from plates to, yes, patch boxes.7

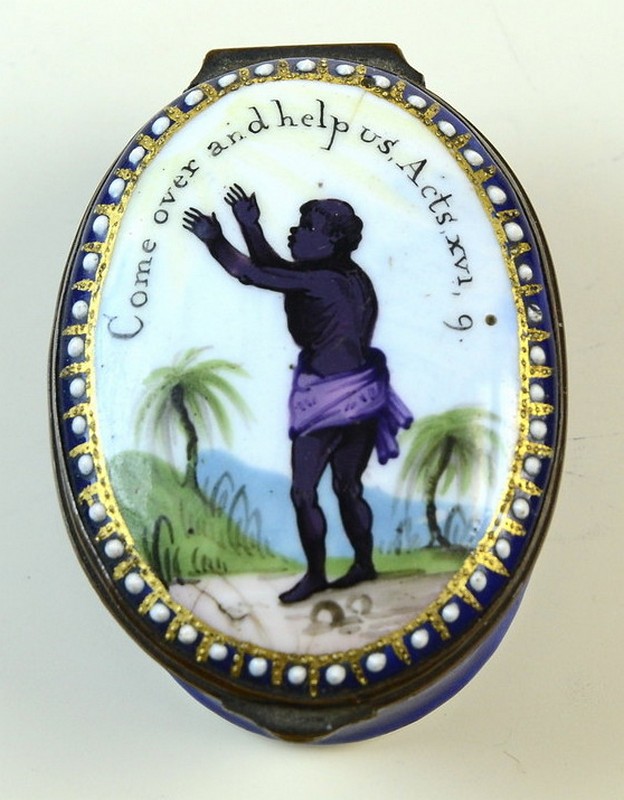

Less easy for us to endorse now is a design that appears to be related to the abolitionist movement, but in fact pays witness to the evangelical missionizing of nineteenth-century Christianity. Pursued with fervour by many in the Christian churches of Europe and America, this movement gave rise to missionary societies, Bible translations, and missionary work across the globe. The box here, showing a black figure with his arms raised in welcome or supplication, references Acts 16.9, in which a vision of a Macedonian appears to St Paul and begs him to come over and help. This Paul does, by preaching the gospel and baptising the newly converted.

Subjects like these should encourage us to reflect yet again on our easy assumption that a patch box was only about patches. At this stage they were a vehicle for a design, a way of selling a functionally unnecessary commodity, a way of leveraging support for ideas and ideals. Despite their old-fashioned name, therefore, by now they were a quintessentially modern item: a mass-produced thing that no one ‘needs’ but that many people want.